What’s Three-Way Match?

Three-Way Match (3WM) Overview

Three-way match, or 3WM, is the process of reconciling three key documents in the procurement process:

Purchase order (PO)

Receipt

Invoice

In order for a PO to be fully reconciled, all three of these documents should agree on the SKU, quantity, and price. Sounds easy, right?

Three-way match is a critical workflow in the financial and supply chain management of companies, and it is essential for both accounting and operations teams to understand its workings and impact.

What documents are involved in three-way match?

Before diving into the reconciliation process itself, let’s define the documents themselves and their uses.

The Purchase Order

The Purchase Order (PO) is the first document in the procurement process. It states the SKUs that are being ordered, the price that was agreed upon, and the quantity of each SKU. It will typically also include a delivery address and expected delivery date, and might include Incoterms (which define the responsibility of the buyer and seller during the import process), payment terms, and discount terms.

The Receipt

The receipt is generated when the buyer takes ownership of the goods from the supplier. Typically this occurs at the buyer warehouse, where they can inspect the goods for any quality issues or damages and complete a full count of what was actually delivered.

Depending on the Incoterms, the buyer may take financial ownership of the goods before they arrive at their warehouse (as is the case with Ex Works). It’s important that the warehouse receiving team make a final inspection of the goods to ensure that they have an accurate record of what was received.

The Invoice

The invoice is the last step in the three-way match process. The invoice is sent by the manufacturer to the buyer and states exactly what was produced and purchased. Depending on the payment terms, the buyer has a limited amount of time make payment (e.g., if the payment terms are “net-30”, the buyer must pay within 30 days of delivery) before incurring penalties or potentially having their goods held by the seller.

The Role of Operations Teams in Three-Way Match

Ops teams are often not involved in the true three-way match process itself, despite coordinating all of the physical movements of goods.

Ops teams will determine the order quantities as part of the planning process, aligning on the right buys based on their forecast, current inventory levels, and expected production and transportation lead times. A purchase order needs to account for both the demand that the company expects to see, and also all variability in the end-to-end supply chain.

Once the order quantities are determined, the team will cut the actual purchase order to the vendor. Typically this involves sending a spreadsheet or PDF to a vendor via email, or transmitting a PO via EDI.

From there, the supply chain team will work with the vendor to ensure that they have the right components to manufacture the items, manage their production schedule, and keep track of the expected receipt date to ensure that the PO arrives on time.

Once the goods are ready for pickup, the ops team will arrange transportation, pickup from the vendor, and delivery to the company’s warehouse. Sometimes this involves spreading a single PO across multiple shipments, or combining multiple POs onto one shipment.

Once the goods are delivered, they will work with the warehouse team to ensure that the goods are received quickly and accurately so that they can be made available for sale as quickly as possible.

The Role of Accounting Teams in Three-Way Match

Accounting is typically responsible for actually completing the match process. Like many accounting workflows, three-way match often happens as part of the month-close process, weeks after the goods have arrived and often without the context and information access that the operations team has.

Ultimately they need to match the same documents that the ops team works with, but they require a level of detail and accuracy that ops doesn’t necessarily need. For instance, it’s common for vendors to have an agreed-upon tolerance for a purchase order quantity. Based on scrap, production runs timing, and material availability, a manufacturer might produce +/- 5% of the exact PO quantity. This is a very reasonable, real-world policy, and companies will agree to pay for what was actually produced within this tolerance.

Accounting, however, must match these documents perfectly. If the purchase order called for 10,000 sneakers and 10,005 were produced, received, and invoiced for, the three-way match breaks. Instead, the accounting team is often forced to update the original purchase order to match what was actually produced. This creates its own set of problems, and makes it impossible to use the PO to gauge a vendor’s true fill rate (since, in order to make the match work, their quantity produced will always be exactly what was on the purchase order).

Accounting must also ensure that the ledger transactions they create match all of the terms of the PO. Is the production quantity actually within the agreed-upon tolerance? Is the company able to pay within the discount window? Does the invoice date align with the transportation milestones and Incoterms?

All of these nuances mean that accounting teams spend a significant amount of time on the three-way match process, despite all of the data being generally available and the real-world movements working smoothly. As companies grow, this process only becomes more burdensome, and many teams are forced to scale their headcount almost linearly with transaction volume.

Why is it so hard?

Even with all those complications, it should be a simple process! There are only three documents, with three criteria; in the most simple case, you have just nine data points. But nothing in supply chain is ever simple… Let’s run through a very common scenario.

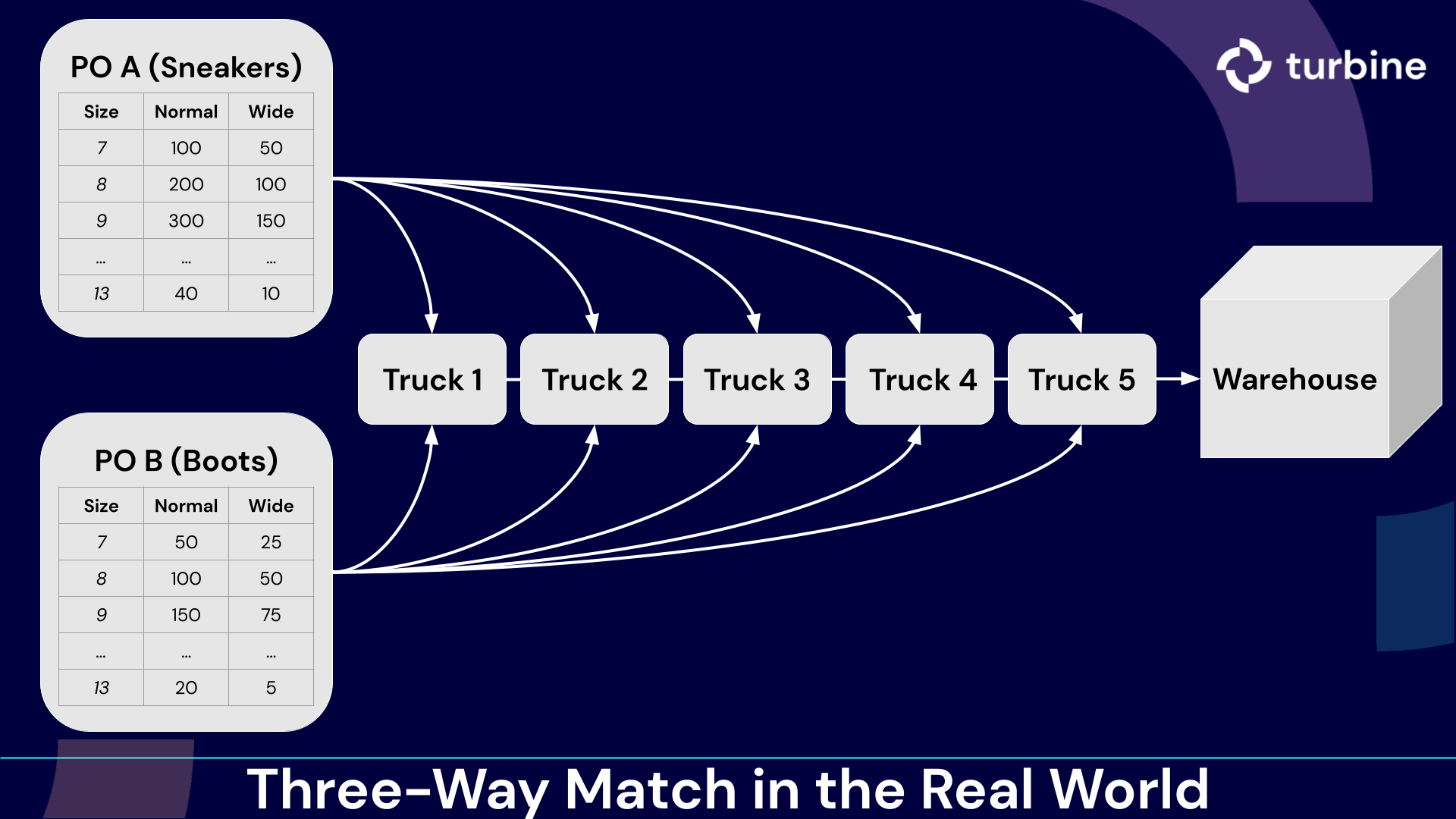

Say you cut a PO for 1,500 sneakers with your manufacturer on January 1st. They receive the PO and make some changes to their production lines to start making your sneakers on February 1st. But, they can only produce 300 sneakers/week. Let’s say 300 sneakers are roughly half a truckload, so you work with your freight broker to secure one LTL pickup for the next five weeks. Now your one PO is spread across five different shipments.

Now let’s say you also cut a PO for 750 boots with a different manufacturer on January 15th. They are speedier with production, and also start production with 1,000 boots/week on February 1st. Boots are bigger and also take up half a truckload, so you coordinate with your freight broker to pick up shipments of 1,000 boots every week on the same truck as the sneakers, delivering to your warehouse a week later. Now you have five different shipments with two POs each.

Finally, let’s say that those POs weren’t just for generic “sneakers” - they were for a specific distribution of ten different sizes and two different widths. Now when your warehouse receives a single truckload, they’re actually receiving one shipment, two POs, and forty unique line items on a single shipment.

Three-way match in the real world can involve exponentially more datapoints

Let’s pause for a moment to appreciate this scenario - the efficient way to transport these goods has resulted in going from one purchase order to two hundred receiving lines over five weeks. And this is with everything running smoothly.

Now let’s say that one of those trucks was delayed a few days due to a driver shortage, so truck 4 arrives before truck 3. And let’s say that truck 3 had the same line items as truck 4, but slightly different quantities. Your warehouse will need to know that this is truck 4 and not truck 3, despite the two having the same PO numbers, the same SKUs, and the same freight carrier.

All of these complications are extremely common, and only get worse as a company expands in vendor base, SKU count, and fulfillment network.

Once the goods land, the ops teams can rest - but the accounting team’s work has only just begun.

How can you improve your three-way match flow?

Process

Three-way match is a process and, as with any process, benefits from taking a holistic view. Most companies have accounting and ops teams working separately from one another, with no regular check-ins and minimal cross-domain knowledge. If you think about three-way match the way that we’ve laid it out here, you’ll immediately see that it’s not just an accounting process - it’s actually an extremely cross-functional workflow.

Consider having your ops and accounting teams establishing a shared inbox for all purchase order messages to ensure that everyone has access to the same information. Move as much internal communications to public channels so that every team can see updates in real-time - not just at the end of the month. For some companies, a monthly (or even weekly) touchbase between teams builds both trust and context across teams and can be a worthwhile investment when things get messy.

Data

Operations systems today generate more data than most teams know what to do with. You can watch your shipment motor down the highway, see port unloading backlogs, or get real-time flight tracking updates. Unfortunately, these systems don’t talk to each other or create feedback loops to help each other get smarter.

While the data warehouse solves some of these problems, ops teams require real-time, high-fidelity data so that they can make decisions in the real-world. Most solutions that exist today are great for reporting, but are too slow to be used in ops workflows.

Tools

There are plenty of tools in the market today that can help with three-way match, but they tend to stick to the same imaginary lines that exist within the processes we’ve described.

On one side you have financial tools: systems that are purpose-built for accountants and offer every transaction and ledger entry under the sun.

On the other you have operations tools: supply chain management and visibility platforms, transportation management systems, and procurement solutions - all of the products that have become part of the Modern Ops Stack.

These tools address two sides of the same coin: financials and cash on one; inventory on the other.

ERPs are supposed to bridge the gap between these two solutions, but lean heavily into the financial side (and often provide a subpar experience for both sets of users). Ask any supply chain manager about their experience with reconciling shipments in their ERP, and you will be met with a grimace.

How Turbine gets to the root of three-way match

Turbine is financial software for companies with physical inventory. We are building a product that addresses both sides of this coin- that serves accountants and ops managers as equal users. Our three-way match process plugs directly into your existing purchase order flows and centralizes all email communications onto the transaction itself, so anyone and everyone on your team knows exactly where to look for the latest updates.

If your company is struggling with three-way match on either side of ops and accounting, we’d love to chat! Sign up for our waitlist or drop us a note at hello@helloturbine.com

Happy reconciling!